Artie is a fully-managed CDC streaming platform that replicates database changes into warehouses and lakes without the complexity of DIY pipelines. It delivers production-grade reliability at scale, without ongoing maintenance.

TL;DR

In this blog, we’ll walk step-by-step through how to build audit log support into your own product. This is the approach we use at Artie to track every change to our pipeline configurations, down to the field level. Our own History Mode feature powers our audit logs, giving customers visibility and helping us debug issues fast.

In this guide you’ll learn how to:

- Build audit logs using Change Data Capture (CDC) + Slowly Changing Dimension (SCD) Type 2 Tables

- Use PostgreSQL JSONB diffs for field-level change tracking

- Combine history tables for related entities

- Mask sensitive data using Go struct tags

- Build a timeline-style audit log UI

Why It Matters

Exposing pipeline history in our product has been a massive unlock for our customers:

- Faster root cause analysis: When something breaks, you don’t want to guess what changed. You want to see exactly who did what, when, and why.

- Compliance and auditing: Many teams need to meet SOC 2 or HIPAA requirements. Having a structured, queryable change history makes it easy to generate audit trails on demand.

- Proactive debugging: Spotting misconfigurations before they cause issues is easier when you have a full timeline of changes.

- Customer support acceleration: Our support team uses this to instantly answer "Did anything change?" when helping customers debug pipeline behavior.

Here’s a scenario we used to see customers run into: someone on their data team made a small change to a pipeline setting, saved it, but forgot to deploy the change. The pipeline was then marked as “dirty” in our system, because it had configuration changes that weren’t live in their actual infrastructure yet.

A few weeks later, an engineer from the same company needed to rotate credentials for a source database. They went to update this in our UI, but they saw a warning that the pipeline had “undeployed changes”. They didn’t know what else had been changed, so they weren’t sure whether it was safe to deploy their credential change.

It became clear to us that our users need to know more than just whether a pipeline has undeployed changes. They need to know what those changes are, when they were made, and by who.

Complications

The challenge in building a thorough audit log is that pipeline configurations are complex and interconnected. In our data model, the configuration for a pipeline is stored not just on a record in our pipeline table but also in a handful of related objects:

- Source and destination connectors (which can be shared by multiple pipelines)

- Source readers (generally specific to a pipeline but can be shared for advanced use cases)

- Per-table configuration (a pipeline can contain many tables)

- Optionally: SSH tunnels or Snowflake Eco Mode schedules (also shareable across pipelines)

We needed a way to track every single change to these components, across all entities, without cluttering our production database. And we wanted it to be fast to query, easy to use, and low maintenance.

For the answer, we turned to dogfooding our own product.

Streaming History with SCD Type 2

Artie's History Mode creates a Slowly Changing Dimension (SCD) table for any source table. Instead of overwriting rows in the destination when an update happens, Artie inserts a new row for every change—capturing the full state of that entity at that moment in time. We support both SCD Type 2 (streaming changes into a history table) and SCD Type 4 (keeping a separate history table in addition to a table that’s kept fully in sync with the source table).

When you enable history mode for a table, Artie creates a __history-suffixed table for it (e.g., pipeline__history). Whenever a row is added/changed/removed from the source table, the history table stores:

- The full row snapshot

- The timestamp of the change

- The operation type: create (

c), update (u), delete (d)

For our use case, we also added user metadata (updated_by) to each of our source tables in order to track who made each change. Here’s a simplified example schema:

Source table: pipeline

Destination table: pipeline__history

In this example, you can see that user 2 created both of these pipelines, and then user 1 deployed the “Postgres to Snowflake” pipeline a few days later.

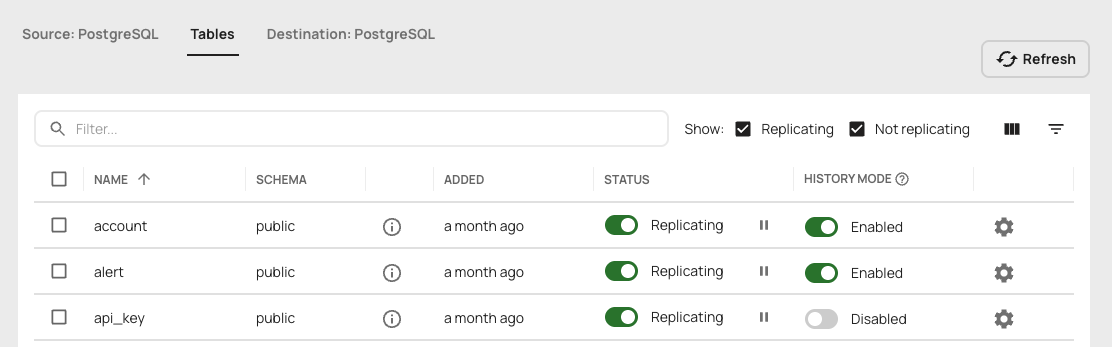

In the Artie UI, you can enable history mode for a table with one click:

Tracking Who Made Changes (Audit Log Actor Pattern)

Every change in our system is attributed to an "actor"—the entity responsible for making the change. The above example showed a simplification of how we track this; in reality, we use a flexible pattern that handles three different types of actors:

type ActorType string

const (

ActorTypeAccount ActorType = "account" // Human users

ActorTypeAPIKey ActorType = "api_key" // Programmatic access

ActorTypeSystem ActorType = "system" // Automated system changes

)

type Actor struct {

Type ActorType

UUID *uuid.UUID // References account or API key

ImpersonatorUUID *uuid.UUID // For admin impersonation

}The Actor is stored as JSONB in PostgreSQL, making it flexible and queryable:

-- Example actor values in the database:

-- Human user:

'{"type": "account", "uuid": "550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000"}'

-- API key:

'{"type": "api_key", "uuid": "7c9e6679-7425-40de-944b-e07fc1f90ae7"}'

-- Admin impersonating a user:

'{"type": "account", "uuid": "user-uuid", "impersonatorUUID": "admin-uuid"}'

-- System automation:

'{"type": "system"}'Why Three Actor Types?

1. Account (human users)

When a user logs into the dashboard and makes a change, we record their account UUID. This is the most common case and provides clear accountability.

2. API key (programmatic access)

Customers can create API keys for programmatic access to our API, e.g. to manage resources with Terraform. When a pipeline is updated via API key, we need to know which API key was used. This is crucial for debugging and security—if an API key is compromised, we can trace all changes it made.

3. System (automated changes)

Some changes are made by our system automatically—for example, when we auto-update a pipeline's last_deployed_at timestamp or when background jobs modify configuration. We track these as system actors and typically filter them out of the user-facing audit log.

Here's the filter we apply at the end of our history query:

SELECT * FROM all_changes

WHERE

updated_by IS NOT NULL AND

updated_by->>'type' <> 'system' -- Filter out automated system changes

ORDER BY event_time DESC;Impersonation Support

The optional ImpersonatorUUID field is particularly useful for admin support scenarios. When our support team needs to help a customer debug an issue, an admin might impersonate their account. The audit log records both:

- Who was impersonated (in

UUID) - Who did the impersonating (in

ImpersonatorUUID)

This provides a complete audit trail for compliance and security purposes.

Displaying Actors in the UI

In our frontend, we enrich the Actor data with human-readable labels. An account UUID gets resolved to a name like "Dana Fallon", and an API key UUID gets resolved to a label like "Production Deploy Key".

Querying Audit Logs with SQL + JSONB Diffs

Tracking history is only half the story. We also needed a clean way to query it for diffs: what exactly changed between version A and version B?

One way to extract these changes would be to query the history table for its raw data and then programmatically diff each row against the same entity’s previous row. We initially explored this approach but found that it would require a lot of hardcoded custom logic related to our data models, it could be computationally expensive, and it would make pagination difficult.

Instead, we had the idea to push this complexity to the SQL layer for better performance and to keep our downstream code simple. By distilling each row down to a json object and diffing those, we could keep the core of the query generic and reusable.

Here’s a simplified version of our diffing query, with more detailed explanations below:

WITH base AS (

-- Get each historical snapshot with the previous state

SELECT

uuid AS entity_uuid,

updated_at AS event_time,

__artie_operation AS operation,

updated_by,

name,

deleted_at,

-- Convert row to JSON, excluding metadata fields

to_jsonb(t.*) - 'created_at' - 'updated_at' - '__artie_operation'

AS row_json,

-- Get the previous row's state using window functions

lag(to_jsonb(t.*) - 'created_at' - 'updated_at' - '__artie_operation')

OVER (PARTITION BY uuid ORDER BY updated_at) AS prev_row_json,

lag(deleted_at)

OVER (PARTITION BY uuid ORDER BY updated_at) AS prev_deleted_at

FROM pipeline__history t

WHERE uuid = $1 -- Filter to specific pipeline

),

changes AS (

SELECT

entity_uuid,

event_time,

-- Detect soft deletes

CASE

WHEN prev_deleted_at IS NULL AND deleted_at IS NOT NULL THEN 'd'

ELSE operation

END AS operation,

updated_by,

name,

row_json,

prev_row_json

FROM base

)

SELECT

'pipeline' AS entity_type,

name AS entity_label,

entity_uuid,

event_time,

operation,

updated_by,

-- Calculate exactly which fields changed and show old/new values

jsonb_object_agg(

diff.key,

jsonb_build_object('old', diff.old_value, 'new', diff.new_value)

) FILTER (WHERE diff.key IS NOT NULL) AS changed_columns

FROM changes

LEFT JOIN LATERAL (

-- Find differences between current and previous JSON

SELECT key, prev.value AS old_value, curr.value AS new_value

FROM jsonb_each(prev_row_json) prev

FULL OUTER JOIN jsonb_each(row_json) curr USING (key)

WHERE prev.value IS DISTINCT FROM curr.value AND key <> 'advanced_settings'

UNION ALL

-- Unnest the advanced settings

SELECT 'advanced_settings.' || key, prev.value, curr.value

FROM jsonb_each(prev_row_json -> 'advanced_settings') prev

FULL OUTER JOIN jsonb_each(row_json -> 'advanced_settings') curr USING (key)

WHERE prev.value IS DISTINCT FROM curr.value

) diff ON TRUE

WHERE

-- Only show rows with meaningful changes

operation IN ('c', 'd') OR

(prev_row_json IS NOT NULL AND row_json IS DISTINCT FROM prev_row_json)

GROUP BY entity_uuid, event_time, operation, updated_by, name

ORDER BY event_time DESC;This query does several clever things. Let's break down some key design decisions:

Why JSONB Diffs Instead of Comparing Columns Individually?

Instead of writing SQL like this:

WHERE old.name != new.name

OR old.status != new.status

OR old.advanced_settings != new.advanced_settings

-- ... 10 more columnsWe convert each row to JSONB and compare the entire object:

WHERE row_json IS DISTINCT FROM prev_row_jsonThe benefits:

1. Schema Evolution

When we add a new column to the pipeline table, the JSONB diff automatically includes it—no query changes needed. With explicit column comparisons, we'd have to update the query every time the schema changes.

2. Maintainability

Our actual query handles 6 different entity types (pipelines, connectors, SSH tunnels, etc.), each with different schemas. Using JSONB means we can use a generic query builder instead of hard-coding column comparisons for each type.

3. Nested Fields

Some of our fields are JSONB columns themselves (like advanced_settings). The JSONB approach handles nesting easily:

SELECT 'advanced_settings.' || key, prev.value, curr.value

FROM jsonb_each(prev_row_json -> 'advanced_settings') prev

FULL OUTER JOIN jsonb_each(row_json -> 'advanced_settings') curr USING (key)

WHERE prev.value IS DISTINCT FROM curr.value4. Null Handling

IS DISTINCT FROM properly handles NULL values (unlike !=), which is crucial for optional configuration fields.

The tradeoff of this JSON diffing approach is that we're serializing rows to JSONB on every query, but the gains in flexibility and maintainability far outweigh the minor performance cost.

Why lag() Instead of a Self-Join?

You might wonder why we use window functions instead of the traditional self-join approach:

-- The self-join approach (we DON'T do this)

SELECT t1.*, t2.* AS prev

FROM pipeline__history t1

LEFT JOIN pipeline__history t2

ON t1.uuid = t2.uuid

AND t2.updated_at = (

SELECT MAX(updated_at)

FROM pipeline__history

WHERE uuid = t1.uuid

AND updated_at < t1.updated_at

)Window functions are cleaner and more efficient:

1. Readability

lag(row_json) OVER (PARTITION BY uuid ORDER BY updated_at) clearly expresses intent: "get the previous value for this entity, ordered by time."

2. Performance

Modern PostgreSQL query planners optimize window functions well. The self-join approach requires a correlated subquery that runs for each row, while lag() is computed in a single pass during the window function evaluation.

3. Guaranteed Ordering

Window functions make the ordering explicit in the OVER clause. With self-joins, it's easier to introduce subtle bugs if the join conditions aren't perfectly aligned.

4. Simplicity

Getting multiple "previous" fields just requires multiple lag() calls. With self-joins, you'd need additional joins or more complex subqueries.

Detecting Soft Deletes

We use a soft delete pattern in our production database—instead of physically deleting rows, we set a deleted_at timestamp. This is safer (you can "undelete" by clearing the timestamp) and better for audit trails, but it means the database operation is actually an UPDATE, not a DELETE.

Artie faithfully replicates this—it sees an UPDATE operation and streams it as such. But for our audit log, we want to show soft deletes as actual deletions. Here's how we detect them:

Step 1: Get the previous deleted_at value using lag()

WITH base AS (

SELECT

uuid AS entity_uuid,

updated_at AS event_time,

__artie_operation AS operation, -- This will be 'u' for soft deletes

deleted_at,

-- Get the previous deleted_at value

lag(deleted_at)

OVER (PARTITION BY uuid ORDER BY updated_at) AS prev_deleted_at

FROM pipeline__history

)Step 2: Detect the transition from NULL to NOT NULL

SELECT

entity_uuid,

event_time,

-- Override operation to 'd' when we detect a soft delete

CASE

WHEN prev_deleted_at IS NULL AND deleted_at IS NOT NULL THEN 'd'

ELSE operation

END AS operation

FROM baseThe logic:

prev_deleted_at IS NULL→ The entity was NOT deleted beforedeleted_at IS NOT NULL→ The entity IS deleted now- Therefore, this update represents a soft delete, so we override the operation from 'u' to 'd'

In summary, the result of this diff query looks like this:

{

"entityType": "pipeline",

"entityLabel": "production-orders-pipeline",

"entityUUID": "123e4567-e89b-12d3-a456-426614174000",

"eventTime": "2024-11-30T15:23:45Z",

"operation": "u",

"updatedBy": {

"type": "user",

"uuid": "d3ae7157-56e6-47ca-a714-89fad6dbf409"

},

"changedColumns": {

"status": {

"old": "paused",

"new": "running"

},

"advanced_settings.flushIntervalSeconds": {

"old": 30,

"new": 60

}

}

}Building a Full Audit Log Timeline Across Related Entities

As mentioned above, a pipeline isn't just a single record in our database. To debug real issues, we need to know what else changed around the same time, across all the pipeline's related objects.

We query history tables for all related entity UUIDs, union them together, and sort by timestamp. This gives us a timeline view of everything that changed:

WITH

-- Find all related entity UUIDs

source_reader_ids AS (

SELECT DISTINCT source_reader_uuid AS uuid

FROM pipeline__history

WHERE uuid = $1

),

dest_connector_ids AS (

SELECT DISTINCT destination_uuid AS uuid

FROM pipeline__history

WHERE uuid = $1

),

-- ... more CTEs for related entities ...

-- Get changes for each entity type

pipeline_changes AS (/* pipeline diff query - see above */),

source_reader_changes AS (/* source reader diff query */),

connector_changes AS (/* connector diff query */),

-- ... more entity change queries ...

-- Combine all changes

SELECT * FROM (

SELECT * FROM pipeline_changes

UNION ALL SELECT * FROM source_reader_changes

UNION ALL SELECT * FROM connector_changes

-- ... more unions ...

) all_changes

WHERE

updated_by IS NOT NULL AND

updated_by->>'type' <> 'system' -- Filter out automated system changes

ORDER BY event_time DESC

LIMIT $2 OFFSET $3;Masking Sensitive Fields in Audit Logs (Passwords, Keys, Tokens)

One crucial challenge with audit logging is handling sensitive data like database passwords, API keys, and tokens. You need to track that these secrets changed without exposing their actual values in your audit logs.

Our approach uses a two-stage process: SQL detects changes, then Go code masks sensitive values.

Stage 1: SQL Detects Config Changes

When connector configurations change, the SQL query detects that the config field changed, but it only returns the raw JSONB blobs (containing encrypted secrets). It doesn't know which specific fields within the config are sensitive:

SELECT key, prev.value AS old_value, curr.value AS new_value

FROM jsonb_each(v.prev_row_json) prev

FULL OUTER JOIN jsonb_each(v.row_json) curr USING (key)

WHERE prev.value IS DISTINCT FROM curr.valueThis returns something like:

{

"config": {

"old": {"snowflake": {"accountURL": "old.snowflakecomputing.com", "privateKey": "encrypted-blob-1"}},

"new": {"snowflake": {"accountURL": "new.snowflakecomputing.com", "privateKey": "encrypted-blob-2"}}

}

}Stage 2: Go Code Processes and Masks

The real magic happens in our Go code that post-processes these history entries. We use struct field tags to mark sensitive fields, then use reflection to mask them:

type SnowflakeConfig struct {

AccountURL string `json:"accountURL"`

Username string `json:"username"`

PrivateKey string `json:"privateKey" sensitive:"true"` // Marked as sensitive!

// ... other fields

}

func maskIfNotEmpty(value reflect.Value) any {

if value.IsZero() {

return value.Interface()

}

return constants.SecretPlaceholder // Returns "••••••••"

}

type Diff struct {

Old any `json:"old"`

New any `json:"new"`

}

// diffStructFields compares two structs field-by-field and returns a map of differences.

// Fields marked with the sensitive:"true" tag will have their values masked.

func diffStructFields(oldObj, newObj any) (map[string]Diff, error) {

result := make(map[string]Diff)

if oldObj == nil || newObj == nil {

return result, nil

}

structType := reflect.TypeOf(oldObj).Elem()

if structType != reflect.TypeOf(newObj).Elem() {

// If the struct types don't match, don't try to diff them

return result, nil

}

oldValue := reflect.ValueOf(oldObj).Elem()

newValue := reflect.ValueOf(newObj).Elem()

for i := range structType.NumField() {

field := structType.Field(i)

oldFieldValue := oldValue.Field(i)

newFieldValue := newValue.Field(i)

jsonTag := field.Tag.Get("json")

if jsonTag == "" {

continue

}

if !reflect.DeepEqual(oldFieldValue.Interface(), newFieldValue.Interface()) {

// Remove `omitempty` and other options from the json tag to get the field name

fieldName := strings.Split(jsonTag, ",")[0]

if field.Tag.Get("sensitive") == "true" {

// Mask the sensitive value!

result[fieldName] = Diff{

Old: maskIfNotEmpty(oldFieldValue),

New: maskIfNotEmpty(newFieldValue),

}

} else {

// Show the actual value for non-sensitive fields

result[fieldName] = Diff{

Old: oldFieldValue.Interface(),

New: newFieldValue.Interface(),

}

}

}

}

return result, nil

}When processing connector config changes, we:

- Unmarshal the old and new config blobs from the SQL result

- Decrypt the encrypted fields (so we can compare them properly)

- Diff the configs field-by-field using reflection

- Mask any fields tagged with

sensitive:"true" - Replace the generic "config changed" entry with detailed field-level diffs

Here's the processing code:

func processChangedColumns(entityType string, changedColumns ChangedColumnsMap) (map[string]Diff, error) {

if strings.Contains(entityType, "connector") {

if config, ok := changedColumns["config"]; ok {

// Unmarshal the configs

oldConfig, err := unmarshalConnectorConfig(config.Old)

if err != nil {

return changedColumns, err

}

newConfig, err := unmarshalConnectorConfig(config.New)

if err != nil {

return changedColumns, err

}

// Decrypt them (so we can compare properly)

if err := oldConfig.Decrypt(); err != nil {

return changedColumns, err

}

if err := newConfig.Decrypt(); err != nil {

return changedColumns, err

}

// Get field-level diffs with masking

configDiffs, err := diffStructFields(oldConfig, newConfig)

// Replace the generic "config" entry with detailed diffs

delete(changedColumns, "config")

maps.Copy(changedColumns, configDiffs)

}

}

return changedColumns, nil

}The Result

After this processing, the audit log shows exactly which fields changed, with sensitive values masked:

{

"entityType": "destination connector",

"entityLabel": "production-snowflake",

"eventTime": "2024-11-30T14:23:15Z",

"operation": "u",

"updatedBy": {

"type": "user",

"uuid": "d3ae7157-56e6-47ca-a714-89fad6dbf409"

},

"changedColumns": {

"accountURL": {

"old": "old.snowflakecomputing.com",

"new": "new.snowflakecomputing.com"

},

"privateKey": {

"old": "••••••••",

"new": "••••••••"

}

}

}We know that:

- The account URL changed (and we can see what it changed to)

- The private key changed (but we don't expose the actual values)

- Who made the change and when

Why This Two-Stage Approach?

Since we support a variety of connectors and need to store different info for each of them, connector configurations are stored in a single JSONB column called config. The SQL query can't easily introspect which fields within that JSONB are sensitive—it would require hardcoding knowledge of every connector type's schema.

By handling it in Go, we get:

- Type safety: We have strongly-typed structs for each connector type

- Flexibility: Adding a new sensitive field is as simple as adding

sensitive:"true"to the struct tag - Decryption: We can decrypt the encrypted values to properly compare them (detecting actual changes vs. re-encryptions)

- Field-level granularity: We transform the opaque "config changed" into detailed "password changed, host changed" entries

Putting It All Together

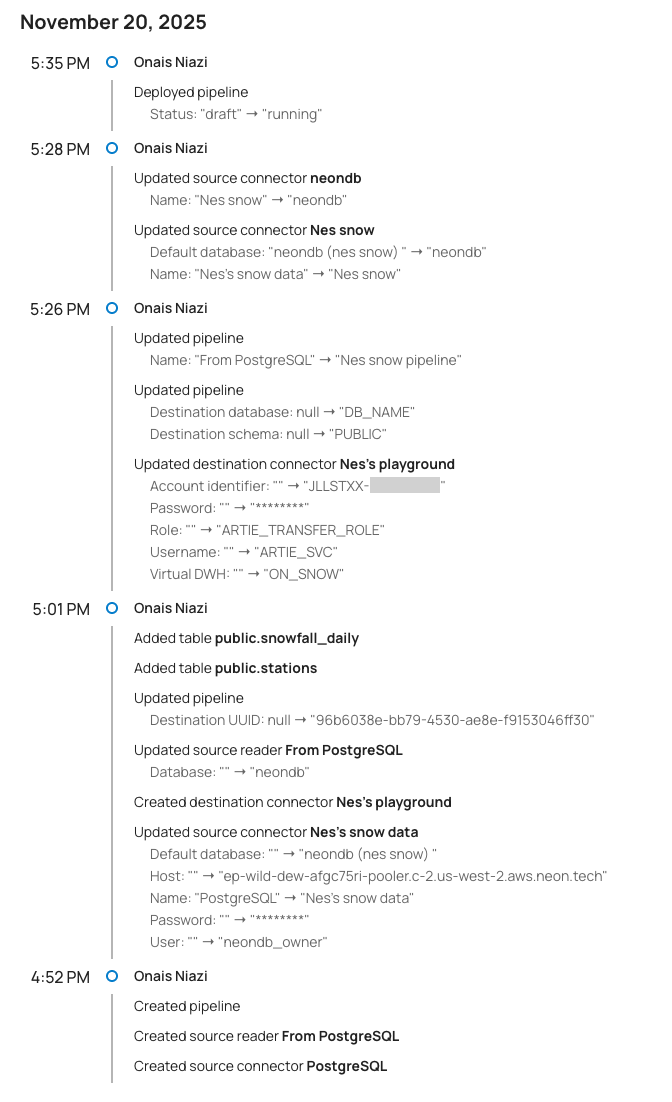

With all of this implemented, we can now display a full audit log of all the changes that have been made to a pipeline:

We build this timeline view with some simple frontend code to group the changes by time and actor:

// Group the history entries by date -> minute -> actor

const groupedHistory = useMemo(() => {

return history.reduce(

(acc, h) => {

const date = dayjs(h.eventTime).format("LL"); // e.g., "October 30, 2025"

const minute = dayjs(h.eventTime).format("h:mm A"); // e.g., "10:00 AM"

const actor = h.updatedBy;

// Initialize the nested objects if they don't exist yet

acc[date] = acc[date] || {};

acc[date][minute] = acc[date][minute] || {};

acc[date][minute][actor] = acc[date][minute][actor] || [];

acc[date][minute][actor].push(h);

return acc;

},

{} as Record<string, Record<string, Record<string, PipelineHistoryEntry[]>>>

);

}, [history]);Trade-offs

If you decide to follow this guide to implement audit logs for your own product, keep in mind that enabling history mode for your tables will increase your billable monthly rows processed with Artie. If you have concerns about potential cost increases, we’d be happy to provide estimates before you turn on history mode.

Additionally, the SQL query we outlined here may start to encounter performance problems depending on the size of your data. If this happens, you may want to optimize further by:

- Adding a view that dedupes the no-op changes so the query doesn’t have to sort through these at run time (e.g. rows where only metadata or system-specific fields changed)

- Adding a background job that does periodic compaction, deleting the no-op change rows from the history table

How To Replicate This (Pun Intended)

In summary, you can add support for audit logs in your own product by following these steps:

- Create a pipeline in Artie that reads from your app database and writes to another database your app can connect to. For example, we use a separate PostgreSQL database in the same cluster as our app DB.

- Make SQL do the heavy lifting: use JSON diffs in your query to isolate changes at the field level, so your downstream code doesn’t need to sift through all the raw data.

- Start with one entity, then expand to related entities.

With this approach, you can unlock support for operational audit logging, compliance tracking, and debugging. If you’re already using Artie, you get these history tables out of the box. If not, this is the exact kind of CDC-powered audit logging you can get without building any of the plumbing.